How Nunavimmiut youth perceive their territory: using film to document landscape sensitivity

Project co-led by Laine Chanteloup, Fabienne Joliet and Thora Herrmann.

Sedentarisation and lifestyle changes have profoundly transformed the Inuit’s relationship to the land. While today, different generations coexist in the shared space of the village, their relationship to the territory, their concept and cognitive structure of what this territory represents, and thus their personal and cultural construction related to it, strongly differ between elders and youth.

Interview with the NUNA project team

I) What is the NUNA project?

This research programme attempts to reveal through Inuit images and words the modern face of what Nunavik is today, a mode of territoriality between tradition and alterity, and to understand different relationships to nature in the context of the creation of national parks. Indigenous and non-native territorialities are imagined to coexist, to interrelate, to be constructed or deconstructed. But what forms do they take concretely and what is the contemporary Inuit sense of territoriality? The objective is to question this in the meaning given by Bonnemaison (1981): to grasp ‘the cultural and emotional vision of the land’.

As regards methodology, understanding native territoriality through Western research is compromised if it is associated with colonialism (Tuhiwai-Smith, 2012). Our project is rather based on grounded theory, which involves using inductive, integrative and intuitive methods, rehabilitating the virtues of empiricism as a source of initial and iterative information. Grounded theory ‘aims to discover theoretical perspectives from reality as it is lived in the field. From this perspective, the reality is continuously being constructed by native people, and the task of the researcher is to study these constructs on the basis of their representations’ (Truchot V. online). So it is from ‘inside’, through the medium of Inuit images to depict their land and to comment on their attachment to it that we are trying to retrospectively extract an ‘internal classification’ of their relationship with the territory, which may be an expression of their cosmology.

The first phase of the NUNA project, carried out from 2014 to 2016, was a research project based on landscape photos taken by the inhabitants of different communities in Nunavik, a project that was started by F. Joliet in 2008 and supported by the French Polar Institute (IPEV). However, few Inuit/Cree adolescents participated in this part of the project despite the fact that the current age pyramid in Nunavik has a very unique profile: 65% of adults are under the age of 29, and 35% of the entire population is between the age of 0 and 14. Moreover, young people’s vision of the territory is very different from that of adults and elders due to changes in mobility, practices linked to the land, and places of birth (elders were born in tents, while today’s young people are born in cities further south or in the villages). For this reason, during the 2015–2016 phase of the project submitted to the Nunavik Human–Environment Observatory, a new method of data collection was envisaged: we organized video workshops for local adolescents so they could depict their relationship to the territory, or ‘Nuna’.

a) Phase 1: 2014–2016

The first phase of the NUNA project obtained the support of two calls for research proposals from the Nunavik Human–Environment Observatory: Tukisik and a post-doctoral position. This phase aimed to develop the research initiated in 2008 by F. Joliet, who organized photo contests in the communities of Umiujaq, Kuujjuarapik, and Whapmagoostui. The post-doctoral student Laine Chanteloup, financed by the Nunavik Human–Environment Observatory, further advanced this project by conducting interviews (16 were carried out in Umiujaq and 15 in Kuujjuarapik/Whapmagoostui) based on the photographs submitted for the contest. An additional 82 new landscape images taken by Inuit and Cree were collected.

The first phase of the NUNA project obtained the support of two calls for research proposals from the Nunavik Human–Environment Observatory: Tukisik and a post-doctoral position. This phase aimed to develop the research initiated in 2008 by F. Joliet, who organized photo contests in the communities of Umiujaq, Kuujjuarapik, and Whapmagoostui. The post-doctoral student Laine Chanteloup, financed by the Nunavik Human–Environment Observatory, further advanced this project by conducting interviews (16 were carried out in Umiujaq and 15 in Kuujjuarapik/Whapmagoostui) based on the photographs submitted for the contest. An additional 82 new landscape images taken by Inuit and Cree were collected.

The images were then used to make two 20-minute slideshows that were created with the communities of Umiujaq, Kuujjuarapik, and Whapmagoostui between 2014 and 2016. The slideshows (delivered in video format) present the images and commentaries accompanied by music. This medium was chosen in order to share the results of the research with the communities (any scientific articles will also be shared, as well as any posters, however, it is difficult for the inhabitants of the communities to take ownership of this type of scientific valorization). This sharing of results was conceived as a tool/deliverable useful to the communities and so well-adapted to the project’s intercultural approach. The aim of these slideshows is indeed to offer them to the communities, who will be able to use them in their cultural centers or during events that present the community from the point of view of the inhabitants. The slideshows will also be shown at the visitor’s interpretation center at the Tursujuq National Park. Schools have also shown interest in using them as educational material.

The first slideshow presentation was organized in Kuujjuarapik and Whapmagostui (see photo 1) on Wednesday, 3 February 2016 at the Triple Gymnasium in Kuujjuarapik. Around 30 people, Inuit and Cree, came to watch the slideshow concerning the communities for three hours in the evening (see photo 2). Feedback, which was very positive, was collected. The audience suggested that the Cree attending add Cree music alongside the Inuit throat singing already incorporated in the film, which they willingly agreed to do.

The first slideshow presentation was organized in Kuujjuarapik and Whapmagostui (see photo 1) on Wednesday, 3 February 2016 at the Triple Gymnasium in Kuujjuarapik. Around 30 people, Inuit and Cree, came to watch the slideshow concerning the communities for three hours in the evening (see photo 2). Feedback, which was very positive, was collected. The audience suggested that the Cree attending add Cree music alongside the Inuit throat singing already incorporated in the film, which they willingly agreed to do.

A second presentation (an invitation from Nunavik Parks) was held Thursday, 4 February for the Harmonisation Committee of the Tursujuq National Park, bringing together key stakeholders from the municipality of Kuujjuarapik, the Whapmagoostui Band Office, the municipalities of Umiujaq and Inukjuak, as well as Nunavik Parks employees and the Québec Minister of Forests, Wildlife and Parks (see photo 3). In this presentation, the slideshow also received a lot of positive feedback, so it was decided that it would be translated to Inuktitut and Cree (with the help of Nunavik Parks) and that the Cree music and Inuit throat singing in the film would also be a way to promote local Nunavik artists. A Cree musician volunteered.

In Umiujaq, two presentations of a slideshow concerning the community were held on Monday, 9 February at the Kiluutaq school. The first was at 1:30 p.m. for all school children (see photo 4). During the slideshow, many reactions were noticeable in the room, particularly in response to images of animals and sunsets. The children also reacted when they recognized the name of someone in their family. The second was held for adults in the evening from 6:00 to 8:00 p.m. Despite blizzard conditions, 20 adults braved the wind to come to see the film, and the elders stayed to watch the projection up to three times. After these presentations, the school and the mayor of Umiujaq requested a version in English, in Inuktitut, and in French so it could be used as an educational tool, and also to present the community to French-speaking tourists. This request arose from an experience with the first tourists to visit the community in the summer of 2015.

In Umiujaq, two presentations of a slideshow concerning the community were held on Monday, 9 February at the Kiluutaq school. The first was at 1:30 p.m. for all school children (see photo 4). During the slideshow, many reactions were noticeable in the room, particularly in response to images of animals and sunsets. The children also reacted when they recognized the name of someone in their family. The second was held for adults in the evening from 6:00 to 8:00 p.m. Despite blizzard conditions, 20 adults braved the wind to come to see the film, and the elders stayed to watch the projection up to three times. After these presentations, the school and the mayor of Umiujaq requested a version in English, in Inuktitut, and in French so it could be used as an educational tool, and also to present the community to French-speaking tourists. This request arose from an experience with the first tourists to visit the community in the summer of 2015.

A third presentation was held on Wednesday, 11 February exclusively for the team at the national park. Since this date, the final versions of the films, including the music requested and the translations in Cree, Inuktitut, and French, have been delivered to the communities. A version of the films was also shown in the Nunavik museum exhibition organized on Inuit land by Grenoble’s Musée Dauphinois. This slideshow can be found below in ‘Documents’.

b)Phase 2: from 2016

b)Phase 2: from 2016

So far three films have been made with Indigenous youth during the video workshops (Figure 1) organized in cooperation with the schools. These films aim to understand young people’s vision of the land.

The first video workshop was conducted jointly with the Badabin school in the spring of 2016 and was aimed at the Cree youth of Whapmagoostui. The students chose to make a film about the ‘First Steps Ceremony’, held to introduce a new-born to the territory and the community. This workshop allowed us to test the methodological protocol and refine it.

The second workshop was held in 2016 with the Asimauttaq school of Kuujjuarapik, and the focus, chosen by Inuit students, was the camps used for traditional activities. The third workshop was held in 2017 with the Arsaniq school in Kangiqsujuaq. These students chose to present hunting and fishing practices and related activities such as sewing.

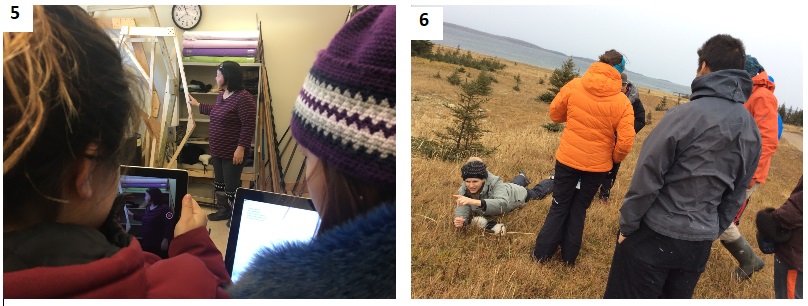

Video is a creative tool, allowing personal expression and the development of critical thinking in the students, who control the whole process after a few training sessions that teach them how to use the equipment (see photos 5 and 6).

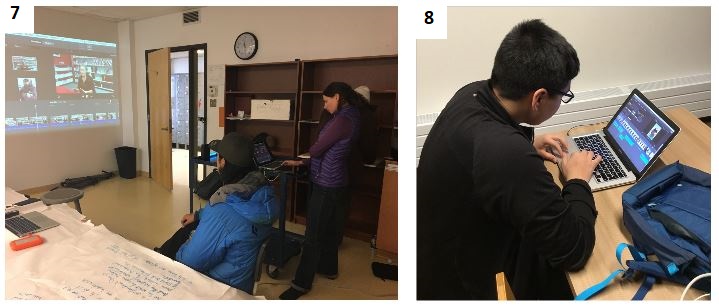

They are the ones who write the script, shoot the film, select, assemble and edit the images, and create the soundtrack (see photos 7 and 8).

In the process, the youths themselves become ‘knowledge collectors’ and interpreters of this knowledge, which puts them in a position of ‘neo-researchers’ co-constructing their knowledge with academic researchers, allowing a sort of decolonization of research. The students were also encouraged to seek out elders to acquire knowledge. This tool respects the transmission of traditional knowledge through the mode of oral history but also opens a space for young people to use contemporary modes of knowledge creation and transmission such as writing and composing electronic music (see photo 9).

Finally, the video gives an inside perspective, allowing the inclusion of subjects that are difficult to address or to grasp by other research methods (e.g. appreciation of the holistic relationship to the environment). Moreover, the video is a tool that offers an unquestionable advantage in allowing communities to claim ownership of the content as well as the deliverable. The short films are left with the communities, who can use them for communication or presentation purposes (see photo 10). For example, the village of Kuujjuarapik showcased the short film created by the students in the community during the inauguration of a recently constructed cinema. The researchers were unaware of this projection and only heard about it in the course of a conversation several months later, learning that this projection had generated a lot of enthusiasm in the community due to its promotion of the work of local youth. The continued life of the short film after the researchers left the village demonstrates the appropriation of the work by the community.

II) Who are the stakeholders and team members?

The NUNA project is the result of close collaboration between a team of three researchers (Laine Chanteloup, Fabienne Joliet and Thora Herrmann) and local schools, organizations, community members and, in particular, local Inuit and Cree students.

III) What is the background to the project?

The NUNA research programme described above is the latest in a sequence of projects that began in 2008. The previous research programmes were funded by different groups of research centers. The chronology and reasoning behind these projects can be traced in the project pages below.

Project Page 2015 ("Tursujuq: un parc national, plusieurs paysages? Celui des Inuit, des Cris et des visiteurs", Fabienne Joliet)