IMALIRIJIIT: measuring the water quality and the temporal dynamics of environmental change using spatial remote sensing

Project co-led by Jean-Pierre Dedieu (CNRS/IGE Grenoble) in France and Esther Lévesque ((Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières) in 2019-2020, Jan Franssen (Université de Montréal) and Jean-Pierre Dedieu in 2018, José Gérin-Lajoie (Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières) and Jean-Pierre Dedieu in 2016-2017.

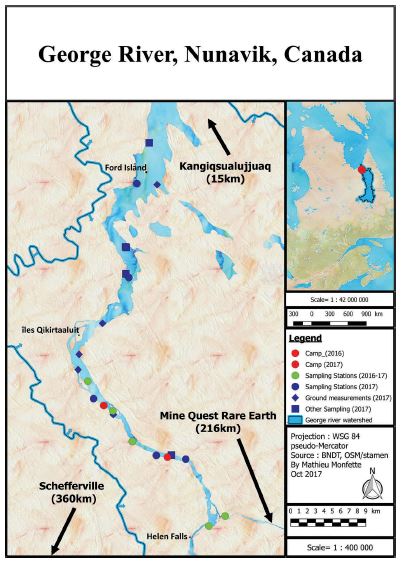

The watershed of the George River (in the Nunavik region of Québec) offers a unique opportunity for a multidisciplinary project investigating human-environment interactions. The initial George River aquatic biomonitoring programme (AQUABIO) was launched in 2016 following a request from the Kangiqsualujjuaq community in Nunavik. The first part of the project involved setting up three science camps: in 2016, 2017 and 2018. From 2018, AQUABIO was integrated in the wider IMALIRIJIIT project (see below). Strictly concerning the hydrology and ecology research, the analyses involved several partner laboratories: Université de Montréal (biology, geography, chemistry), Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières, and the Institute of Geoscience and the Environment (IGE) in Grenoble, associated with the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS). The results from previous years are available in the annual project activity reports and documents in the links below. The current project has two stages. The first consists of completing the in-situ campaigns on river hydrology by taking measurements from buoys left in place over the summer months and coupling these with the analysis of optical satellite images (Landsat-8 and Sentinel-2). The second is to apply a multitemporal remote sensing study (Landsat-5 and 8) that covers the changes in vegetation over the entire watershed over a period of 30 years (1985–2000-2015). The final stage focused on produce detailed vegetation mapping in order to qualify and quantify the zones of vegetation densification over the determined three-time periods. Field measurements were carried out in the summer of 2018 will supplement the remote sensing analysis. This ecological study is fundamental to better understand the impact of climate change in the Arctic (‘Arctic greening’) and the consequences that these vegetation changes have on local populations (e.g. in terms of natural food resources, as berries).

- Interview with José Gérin-Lajoie, Co-leader of the IMALIRIJIIT project

-

- How did the project come about?

The George River basin covers a vast area (42,000 km2 in area and 565 km in length) that extends from the boreal forest in the south to the Arctic in the north. The territory is an important site for traditional activities, such as hunting, gathering, and fishing, practiced by the people of Kangiqsualujjuaq. Concerned about the potential impacts of a proposed rare-earth mine in the upper watershed of the George River, the community wanted to implement its own independent environmental monitoring programme with a long-term perspective. The main aims of the project are to document water quality before and after the mining operations begin and also to support the development of skills at a local level. This led to the community-based aquatic monitoring programme of the George River, IMALIRIJIIT (‘those who study water’ in the Inuktitut language), which was launched in 2016 as a pilot project. This programme prioritizes an applied, local approach to allow community-based and long-term environmental monitoring of the George River and involves young people as well as elders, local experts, and researchers. The focus of the project arose from the community itself in 2015 after a consultation process with local organizations during the course of which several possibilities were proposed, including water quality linked to the development of the mine.

-

- Who are the stakeholders and the team members?

The IMALIRIJIIT project team is multidisciplinary and has strong links with the community through a variety of partnerships between the inhabitants and researchers from different universities, government agencies, local experts and non-profit organizations.

The team consists of:

- - José Gérin-Lajoie (co-leader of the IMALIRIJIIT and the AQUABIO projects and professor at the Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières)

- - Gwyneth A. MacMillan (co-leader of the IMALIRIJIIT project and post-doctoral student in biological sciences at the McGill University, Montreal)

- - Hilda Snowball (co-leader of the IMALIRIJIIT project and the mayor of Kangiqsujuaqlujjuaq)

- - Jan Franssen (Co-Porteur de l'APR AQUABIO, Professeur au département de géographie de l'Université de Montréal)

- - Jean-Pierre Dedieu co-leader of the AQUABIO project and deputy director of the Nunavik Human–Environment Observatory and senior researcher at the CNRS/IGE Grenoble)

- - Marc Amyot (biological sciences professor at the Université de Montréal)

- - Esther Lévesque (environmental sciences professor at the Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières)

- - Thora M. Herrmann (associate geography professor at the Université de Montréal)

- - Eliot Sicaud (Master’s student studying hydrology and environmental dynamics of the George River at the Université de Montréal)

- - Geneviève Dubois (youth coordinator since 2018)

- - Megan Gavin (student in the environmental technology programme at the Nunavut Arctic College)

- - Xavier Dallaire (Master’s student studying population genetics of the Arctic char at the Université Laval)

- - Émilie Hébert-Houle (former project co-leader and youth coordinator 2016–2017)

- - Mathieu Monfette (Master’s student studying hydrology dynamics of the George River at the Université de Montréal)

- - Justine A. Rowell (Master’s student in chemistry at the Université de Montréal)

- - Tim Anaviapik Soucie (Inuk researcher involved in community-based monitoring of water quality, Port Inlet, Nunavut: see facebook page dedicated to the project)

- - Eleonora Townley (teacher at the Uluriaq school in Kangiqsujuaqlujjuaq, president of the youth committee, co-manager of the scientific station at the Nordic Study Centre in Kangiqsualujjuaq)

- - Jeannie Annanack (membre du Youth Committee et co-gérante de la scation scientifique CEN à Kangiqsualujjuaq)

- - Johann Housset (collaborator in the analysis of vegetation dynamics remote sensing)

- - Elise Rioux Paquette (education officer for Nunavik Parks)

- What is your approach? How are you working with the local community?

The priority objective of the IMALIRIJIIT project was to implement a monitoring programme that was community-based, collaborative and long-term in the environment of the George River watershed, as requested by the local community. This resulted in the establishment of scientific camps in the area in 2016, 2017 and 2018. The mission of these camps was both scientific and educational, with the goal of training young Inuit in scientific methods through a concrete, field-based approach. This ranged from using rigorous sampling methods to collect samples for testing water quality (e.g. chlorophyll concentration, pH level, conductivity, etc.), thus reinforcing local water-quality monitoring capabilities, to the study of contaminants in traditional food sources. Continuity was a key concern from the outset in order to build a relationship of trust and ensure long-term, productive collaboration.

A second objective was to study both water quality and environmental changes at the scale of the entire watershed using remote sensing. In-situ measurements contributed to verifying three parameters concerning water quality in the watershed: water transparency, productivity of the aquatic ecosystem (chlorophyll-a) and temperature. Traditional environmental knowledge provided another tool for measuring changes regarding the populations visiting the George River watershed and for determining where to set up the sampling sites.

Since 2016, the community of Kangiqsualujjuaq has been very involved in the logistical and financial aspects of the project. The funding for the project was provided jointly by the community and the researchers. The local youth, as well as the municipality (the Arctic village of Kangisualujjuuaq), have been active in the project from the outset.

- Can you single out any key highlights?

The ceremonies at the middle and end of camp every year really reflect the engagement of the young participants as budding scientists. Their enthusiasm also shows in their very positive comments during the camps: for example, “You always have cool stuff.” “I love science.” This interest in the camps is continually growing: now they’ve started asking when the next one will be and sharing their suggestions for the next camp. Each year the community increasingly takes ownership of the project, making its perspectives long-term and sustainable. The project is a good example of an emerging community-based approach and is developing into a research programme of increasing significance.

-

- What are the results so far?

The lichen samples collected around the village and the watershed have demonstrated their effectiveness as bioindicators of air quality. New data on certain plants and animals is currently being analysed in order to provide a reference point for the natural concentration of metals in the Arctic environment. These indicators will allow the monitoring of water quality, plants and animals in a context of climate change and resource exploitation. The remote sensing data aims to measure vegetation changes over the last 30 years and to extrapolate certain parameters regarding water quality at the scale of the watershed. However, a number of challenges remain.

During the science camps, local young people have been introduced to various environmental and earth science disciplines and have learned about scientific and sampling protocols. Participating in different types of scientific measurements with adults and elders from the community as well as researchers has had a positive impact on young Inuit and their perception of science. The camps have also strengthened the links between them and their elders, as well as with researchers. The quality and success of the camps have been publicly recognised by the members of the community.

The practical, territory-based approach of the IMALIRIJIIT project has allowed the Kangiqsualujjuaq community and our research team to combine Inuit and scientific knowledge and to demonstrate how they are complementary (e.g. observation, analysis, resolution of problems). All of these aspects have promoted better engagement in the learning process of the young participants. The creation of an interactive map will provide a useful multimedia tool that promotes the further democratization of knowledge, for Inuit communities as well as the scientific community.

-

- Links to websites and publications created for this project